In 2025, we had the pleasure of returning for our second year to help organize the robotics course at the University of Eastern Finland, led by Ilkka Jormanainen. From the previous years, we have written about our involvement in the course and about the open-source course, Robotics and ROS 2 Essentials, that was published as a result of the collaboration.

This year, we wanted to offer a different perspective by giving a student an opportunity to share their experience and details about their course project in their own words. Sıla Uluyol, an Erasmus student, kindly wanted to tell her story. Read it below!

Sıla Uluyol

BSc Computer Eng. at Ankara University

When Your Robot’s Enemy is a Plank: A Path Planning Story

When I packed my bags in Turkey to embark on my journey for my exchange semester at the University of Eastern Finland (UEF), I had a very specific mission: I wanted to move beyond pure software and finally touch the hardware. I chose UEF specifically for its Robotics curriculum. Little did I know that my biggest challenge would not be the math or the coding but a far more stubborn enemy. Every good story needs a villain, and mine turned out to be low-lying planks.

The Foundation: RXR Course and Henki Robotics

Professor Jormanainen’s Robotics and Robotics & XR courses were exactly what I came for, and what made them particularly valuable was Henki Robotics’ participation and their open-source materials hosted on GitHub.

The repository solved a common problem in hardware courses: the gap between “here is the theory” and “now make it work on actual hardware.” Setup instructions were clear and configuration examples were provided. Each exercise built incrementally. Exercise 5, for example, walked through implementing a straight-line planner before expecting you to tackle more complex algorithms. The repository included working launch files, parameter configurations, and helper functions. When something failed, you could easily isolate whether the issue was your algorithm or a ROS 2 configuration problem.

The course used learning diaries to document your process, and it was the most rewarding practice I still use for other studies. This became such a habit that I started a blog, aiming to write more about my learning journey and helping others along the way.

The Project: Cost-Aware A*

The project brief was straightforward: replace the straight-line planner from Exercise 5 with a more complex algorithm such as A*, Dijkstra, or a custom solution. Since the course itself was built with building blocks, I already had everything I needed to experiment freely. And I do mean straightforward because Henki Robotics’ repository had given me a fully working Exercise 5 implementation as a foundation, “replace the planner” was an invitation to experiment, perfect for a beginner.

After a short bit of research, I chose to go with A* and integrated it with Nav2’s Global Costmap by making it cost-aware. Instead of treating all free cells equally, the algorithm would weight its pathfinding decisions based on costmap values to naturally avoid high-cost areas (obstacles).

A* is a pathfinding algorithm that finds the optimal path by minimizing a cost function f(n) for every node n:

f(n) = g(n) + h(n)

Where g(n) is the actual cost from the start node to the current node, and h(n) is the estimated cost from the current node to the goal. The algorithm uses a priority queue to always explore the most promising node first that is the one with the lowest f(n) value.

The standard A* implementation treats movement between cells uniformly. Moving from one free cell to another costs the same regardless of what is nearby. This works for simple obstacle avoidance where cells are either blocked or free, but it ignores valuable information: the costmap does not just tell you where obstacles are, it tells you how dangerous each area is.

My cost-aware implementation changes the traversal cost calculation. Instead of a fixed cost per move, entering a cell costs:

Traversal Cost = 1.0 + (Cell Cost / 10.0)

Where Cell Cost comes directly from Nav2’s costmap values (0-255). Cells near obstacles have higher costs. Cells far from obstacles have lower costs. If a cell’s cost exceeds 254, the traversal cost becomes infinity resulting in the algorithm not considering that path.

This means the algorithm naturally prefers paths that maintain distance from obstacles, even when a tighter route technically exists. The heuristic function h(n) uses Euclidean distance to estimate remaining cost to the goal to make sure A* remains admissible.

The implementation integrates directly with ROS 2’s Global Costmap. Helper functions convert between world coordinates and grid coordinates. The algorithm extracts the costmap metadata and uses it to navigate the 2D grid structure while respecting the environment’s geometry.

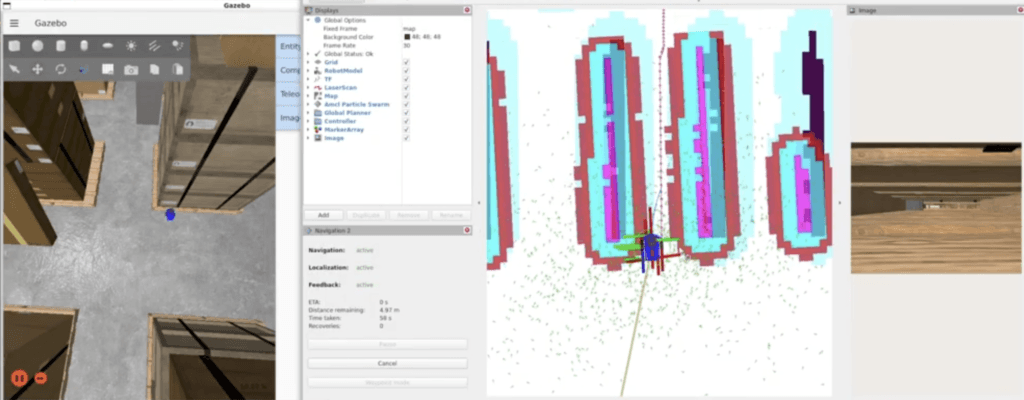

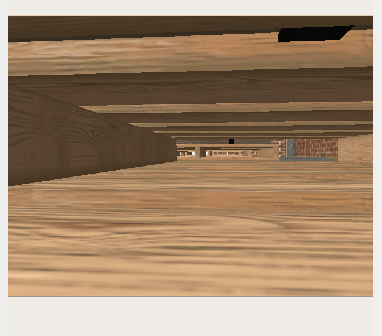

The Test: When Theory Meets Reality

After many attempts to implement the algorithm, finally, the implementation was complete and it was time to test it out. I launched the simulation, gave the robot a pose estimate, and sent it a navigation goal through a relatively simple environment with plank obstacles scattered around. I watched the robot’s camera feed on the left and checked the map on the right with rushing excitement. The path was, indeed, generated! What a moment! It was as if I was watching Neil Armstrong step onto the Moon for the first time ever!

Well… then the robot just crashed into one of the planks right after. I checked my algorithm several times to change and find whatever was causing this. Then I checked what the camera was showing, and there they were the villains of this story: low-lying planks.

I checked the console logs right after and saw the harsh truth:

[planner_server]: GridBased: failed to create plan... Aborting handle.[behavior_server]: Running backup[behavior_server]: Collision Ahead - Exiting DriveOnHeading

After the collision, the planner would fail to generate recovery paths and the robot would attempt backup maneuvers, but the local costmap would abort those too. Stuck in a failure loop, mission aborted.

I turned to my A* implementation again and this is where the structured repository proved its worth. Because Henki Robotics’ materials had cleanly separated algorithm logic from ROS 2 configuration, I could be fairly confident the bug was not buried in a launch file or a parameter I had not touched. The cost function must have been too restrictive. Maybe the algorithm was treating areas near planks as completely impassable, even when they were technically navigable.

I replaced the exponential penalty with linear scaling. Now, instead of costs exploding near obstacles, they would increase gradually. This should allow the planner to consider tighter passages to avoid the villain.

I rebuilt, relaunched, and set a new goal. The robot soon after crashed into the same plank, again.

Then I realized I had misdiagnosed the situation. The problem was not the cost function. The planner was generating paths through areas it thought were empty. The issue was much deeper: the costmap itself did not know the planks even existed.

I dove into nav2_params.yaml and started adjusting values. The planks were low, so maybe min_obstacle_height was filtering them out. I lowered it from 0.1 to 0.05 meters, this should make the sensors register shorter obstacles.

This alone did not fix the issue, so the next step was to increase the safety margins. I changed inflation_radius from its default to 0.5 meters in both the global and local costmaps. This would create a safety zone around low-lying planks so the robot would not attempt to go through them.

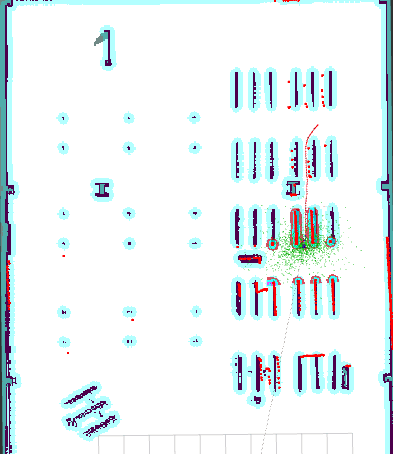

I rebuilt, relaunched, and sent a goal. The planner generated a path. A very long path.

The robot planned an absurd detour around obstacles that should have been easily navigable. The inflated boundaries of the planks overlapped, which forced the algorithm to route around the entire sections of the environment.

The solution was not a single parameter change but finding the balance between three parameters. I needed the costmap to:

- Actually detect the low planks

- Treat them as obstacles to avoid

- Not inflate them so much that valid paths disappeared

The final configuration was:

- min_obstacle_height (global_costmap / obstacle_layer): Lowered the sensor filter threshold from 0.1 to 0.05 so planks would register as obstacles.

- inflation_radius (both costmaps): Reduced from 0.5 to 0.35 to correct over-corrected value and open up narrow passages.

- cost_scaling_factor (both costmaps): Increased to 4.0 from 2.0. Higher scaling meant costs dropped off faster within the 0.35m inflation radius.

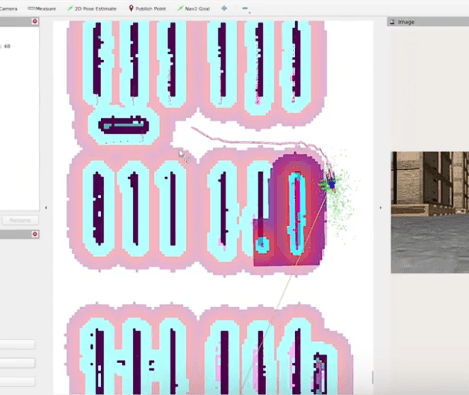

I rebuilt, relaunched, and sent a goal through a passage between planks.

The planner generated a reasonable path and started moving. It approached the first plank, adjusted its trajectory, and navigated around it cleanly. Then the second one, and finally passed through the narrow gap.

It reached its goal: the villain was defeated.

Lessons beyond Code

During this process, the most time-consuming part, however, was not the debugging of the planks. It was not the implementation of A* or the parameter tuning. It was the cycle that came after every single change:

- Close Gazebo

- Close RViz

- Terminate multiple ROS 2 launch processes

- Restart the entire navigation stack

- Send a new navigation goal

- Observe the result

- Repeat

Additionally, RViz and Nav2 components would flood the console with hundreds of INFO-level messages per second. Buried somewhere in this avalanche would be that one critical line I actually needed. Finding that line required me to either copy the entire terminal and paste it into a text editor and use Ctrl+F. Every single time!

This project taught me more than path planning or ROS 2 navigation. The unexpected lesson was about development tools and automation. If I were to do this again, I would spend some time building automation: a bash script to reset and relaunch everything with a single command, log filtering configured, a parameter testing framework.

The RXR course at UEF, supported by Henki Robotics’ materials and Professor Jormanainen’s structure, gave me exactly what I came for: hands-on robotics experience where I owned the problem completely. When you are three hours deep into a debugging spiral over planks, you do not want to wonder whether your ROS 2 config is broken too. The clean separation in Henki Robotics’ repository meant I could direct my focus exactly where it belonged: at my own experiments.

I am forever grateful for the experience Henki Robotics enabled, and doing it all open-source means any student, anywhere, can pick this up and build on it.

And the planks? They were, of course, defeated in the end.

- Check out the project repository from here: ros2-path-planner-project

- Connect with me on LinkedIn!

- See the video of final project results below: